There are films and there are filmmakers that create an everlasting stamp on our mind. We may not agree but the mainstream media has an undeniable effect on our thoughts, mindset, and the consequences.

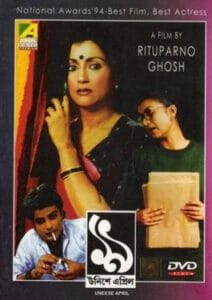

It can be unanimously testified that Bengali cinema, after Satyajit Ray’s death in 1992, regressed into a slump of mediocre to trash films. With the deluge of daughters-in-law (read Boro Bou, Mejo Bou, Sejo Bou) and existential questions as movie titles( read Baba keno Chakor?) ruling the box office the industry, the viewers required a sensible break. And it was at this crucial juncture we met Rituparna Ghosh. To be honest, I have admired the orator and author in him more than the filmmaker he was, but I can never deny the fact it was one of his movies that for the first time showed me a different side to motherhood or womanhood. It was one of my first lessons in feminist outlook. And today on 31st August, his 60th birthday I offer my humble tribute by discussing that masterpiece – Unishe April.

He was always an enigma within the straight-laced and upright Bengali society with an “effeminate” swish of hand, an “unmanly” voice, and straightforward talk. It is only appropriate, then, that Ghosh made his professional debut with Unishe April, a film that challenged ideals of motherhood, juxtaposing the idea of a woman with her roles in an Indian society.

The story

Unishe April, a film set in a South Kolkata residence on a rainy day, depicts the mother, Sarojini (an award-winning classical dancer played by Aparna Sen), and her daughter, Aditi (a recent medical graduate played by Debasree Ray). Sarojini draws happiness from her profession and would never jeopardize it. After her father’s death, Aditi grew up in a boarding school with no attachment to her mother. The mother-daughter conflict arises from the daughter’s repressed anguish over losing her father as a kid and the consequent vilification of her mother.

The resentment turns fatal and Aditi attempts suicide after a breakup on a night washed out by a terrible storm. The failed suicide attempt eventually opens all the floodgates. Twenty-six years of unspoken dialogue are released, and something unparalleled in Indian cinema occurs: a daughter challenges her mother’s capacity for giving, loving, and caring. In response, a mother doesn’t cut a sorry figure but reveals her late husband’s mediocrities and then goes on to discuss their disastrous marriage.

A fresh perspective towards Motherhood and womanhood

Sarojini is hardly the perfect mother, wife, or widow in the context of Bengali cinema and wider Indian cinema. As a Hindu widow, she defies the norm by not embracing white attire. Instead, she is a dancer, clothed in magnificent saris, her forehead shining with a large red bindi, and always unapologetically joyful in her celebration of life. In the early days of the Nineties, having the female lead of a film be an absentee mother who does not fully participate in child rearing was nothing short of revolution.

An estranged relationship

We can also see a certain sense of muted jealousy of Aditi towards her mother, for Sarojini is everything that she is not – desirable, passionate, and stronger woman. Three decades back when the queer Bengali filmmaker made this movie treading such concepts was courageous, to say the least.

Woman Beyond Motherhood

This was a movie that for the first time showed me celebrating a woman who was not defined by her relationships. She might be a mother or a wife but she is also an individual who has her ambition, who cannot be bound by the husband’s lack of ambition. Her success does not lie in her sacrifices but in her achievements. Sarojini’s passion and her dedication beyond her relationships were something that I looked up to. This in itself was a revelation considering how the mothers were portrayed on screen during that era. In that context, Unishe April provides a great feminist interpretation of the film text.

However, in my opinion, the film’s greatest significance is that the writer-director made no pretense of glorifying or exalting the institution of motherhood while punishing and demeaning the individual women who engage in it. This was perhaps one of the first films to address motherhood theory, which investigates motherhood as an institution, an experience, and an identity. A story that went beyond the whitewashed imaginations of the mothers and daughters as entities.

It upholds the tragedy of a woman misunderstood by her daughter simply because her love does not fit into the idealised mother-love – which is often synonymous with sacrifice, the loss that becomes strangling in the process. Thirty years later I can relate to it more than ever.

Patriarchy and flawless Parents

The flashbacks, told from Sarojini’s point of view, reveal the power dynamics that exist between a married couple under a patriarchal order in which the husband is the primary breadwinner and the wife merely supplements his income if she earns anything at all. This demonstrates that even with a sizable financial contribution, the urban, sophisticated Indian lady is not immune to the patriarchal power structure in the household. And with that reveal it brings forth the vulnerability of the parents.

Emotions such as sadness, envy, and desertion in these stories prompt the viewers to consider their limitations in picturing parents as immaculate entities and prompt us to reflect on our beliefs. Only a master storyteller like Ghosh could present the layering of emotions that humanizes all the interactions and separates them from other clichéd portrayals.

At a point, Sarojini says that, despite falling in love with her late husband (Aditi’s father), she never felt appreciated or understood in the marriage. This is the story of so many women trapped in a thankless wedding where they sacrifice their career, and happiness for family.

Though the movie seemed to be from the point of view of Aditi, it is Sarojini’s struggle that has always affected me. Manish, her late husband, his presence in an unequal marriage and his everlasting presence even after his death is Sarojini’s personal battle. The one she cannot win nor lose.

In the scene where Sarojini confesses how she believes she was not destined for marriage since her creative sensibilities were not made to be domesticated, one actually feels her helplessness of being trapped by societal norms.

Conclusion

I can go on and on about this movie but the best thing you can do today is to watch Unishe April on your own. This beautiful gift of a movie from a filmmaker who wore his sexual identity with élan spoke his mind and startled viewers with the portrayal of insightful human relationships that will always remain special.

–X–

This post is a part of Blogchatter Half Marathon 2023